Last updated on July 4th, 2023 at 04:59 pm

If you were given a free ticket to attend the show of Africa’s number one magician, would you accept it? Well, don’t bother responding. Read my previous post to relive the debut show by Africa’s number-one magician.

In today’s post, I’ll introduce you to one of philosophy’s most intriguing puzzles! Some of these puzzles you may have seen before, but I bet you ignored them once you tried to analyse the ramifications of your answer. The philosophical puzzles we’ll be talking about today belong to a category called Trolley Problems.

Trolley problems are not frustrating

Trolley problems are not as frustrating as most people think. A trolley problem can easily be recognized if you have ever received a question of the kind, “If you were in a situation where you had the power to save only one person, would you save your mother or your wife?”

What exactly is a trolley problem? A trolley problem is a philosophical thought experiment that requires you to decide between two offers, where choosing any offer benefits you directly but indirectly causes unintended harm. I know, it sounds complicated. No, not exactly.

They are not tricky

A typical reaction when you hear about a trolley problem for the first time is to become cautious and suspect the question being asked is a trap. Consider the question posed in the introduction of this post. If you were in a situation where you had the power to save only one person, would you save your mother or your wife? You may suspect that whatever response you provide will be used against you. Any offer you settle on in order to fulfil a moral principle somehow exposes a breach of another moral principle. This is a moral dilemma in the purest sense.

Trolley problems are useful in philosophy

Many individuals regard these topics as impractical, pointless, and time-consuming since they never address any real-world problems. This is where a lot of people fail to understand why trolley problems exist. In philosophy, trolley dilemmas are useful in a field of ethics known as metaethics. In contrast to how we should behave morally, metaethics focuses on the language of ethics (or morality). Similar to how science studies the natural world, metaethics studies morality. It is preoccupied with concerns like, “What is the meaning of good?” Is morality objective? What is truth, etc.? Its goal is not to instruct you on how you should behave morally.

Your answer is not that important

In addition, if you’ve ever tried to provide an answer to a trolley problem, you know that it’s more pressing to provide the justification for your answer than the answer alone. Your questioner will almost certainly ask, ‘Why?’ after you have given your answer.

No matter how correct or incorrect your response is, trolley problems don’t give a damn. The emphasis is on why you offered that particular answer. This is why philosophers become frustrated when, instead of answering the problem, you try to alter the trolley problem to give you a perfect condition to solve it.

One moral principle, different moral judgements

Someone may respond, “I can save both of them,” in our example. “I’ll return to save my wife after saving my mom.” That seems admirable and virtue-filled. However, such protests and adjustments dismiss the lesson taught by trolley problems. Trolley problems teach us a very crucial lesson about our moral inclinations.

They reveal how our moral tendencies are not universal but vary depending on the context. Trolley problems were created to demonstrate that, in identical moral dilemmas, our moral judgements are influenced by a variety of considerations in addition to moral principles.

Origins of the trolley problem

The trolley problem was initially put up as a thought experiment by English philosopher Philippa Ruth Foot in 1967 to highlight a point in the debate concerning the ethics of intent. This was to show the distinction between what we plan to happen and what happens as a result. This thought experiment was later used by philosopher Judith Jarvis Thompson in her 1976 article, “Killing, Letting Die, and The Trolley Problem.” Judith was discussing whether it was generally better or worse to murder someone than to let them die.

Situation 1 - Letting die

Let’s use a simple example to illustrate the point of killing a person versus letting a person die. Imagine, if you will, that on a Saturday morning, you are strolling by the beach. You are enjoying the breeze, the quiet, and the morning sun. You are the only person there at the beach right now until you suddenly hear a man’s frantic cries in the distance.

Turning in that direction, you spot a hand waving out of the water. You notice instinctively that someone is drowning. Fortunately, you are an excellent swimmer and can save this poor man. You’re familiar with this beach. Swimming to the drowning man’s location is simply like another day of practice (here comes the question, so pay attention). Did you kill the man if you stood by and did nothing as he drowned? You don’t need to respond right away, but make a note of the query.

Situation 2 - Direct cause

In another situation, situation 2, assume you were on the boat with this man. Suddenly, you push him into the water, and he drowns. Did you murder him? In this second scenario, it is easy to conclude that you killed the man. But as we respond to the first scenario, the language becomes more confusing.

The two typical responses to situation 1 are yes and no. Yes, as it was your moral duty to assist the drowning man, but you chose not to. And no, I wasn’t the cause of the drowning; I just happened to see the man drowning.

Passive problems

It is this murkiness that the trolley problem seeks to expose. A trolley problem is a kind of moral dilemma that aims to examine how the roots of our moral standards differ in similar instances of the dilemma. It also demonstrates why some moral standards you uphold do not necessarily hold true in other circumstances.

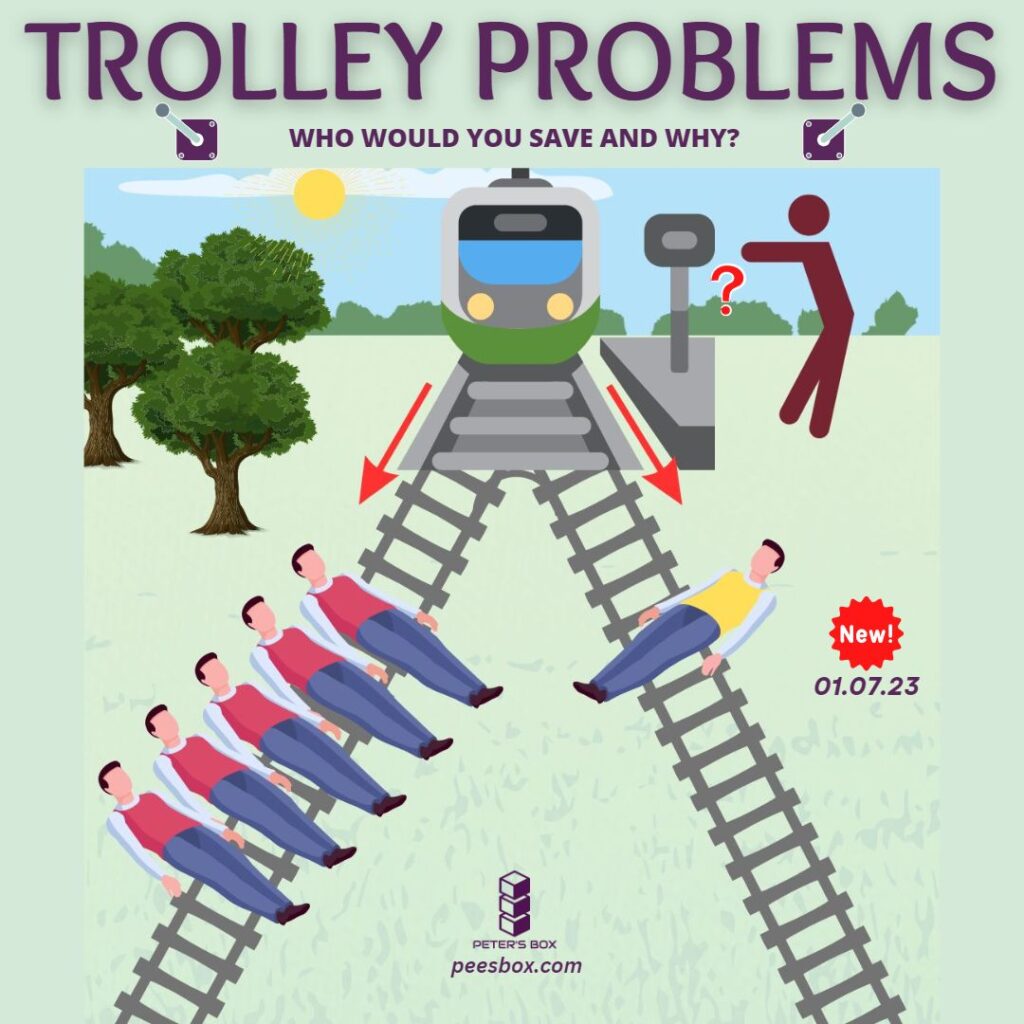

Do you now see why trolley problems are not active problems? They are oblivious to your decisions. The trolley problem can take many different forms, but the one depicted in the flyer of this post is the most straightforward and most commonly used example in philosophy. Check it out if you haven’t already, since we’ll be addressing it in future posts.

The trolley problem

Our first trolley problem goes like this:

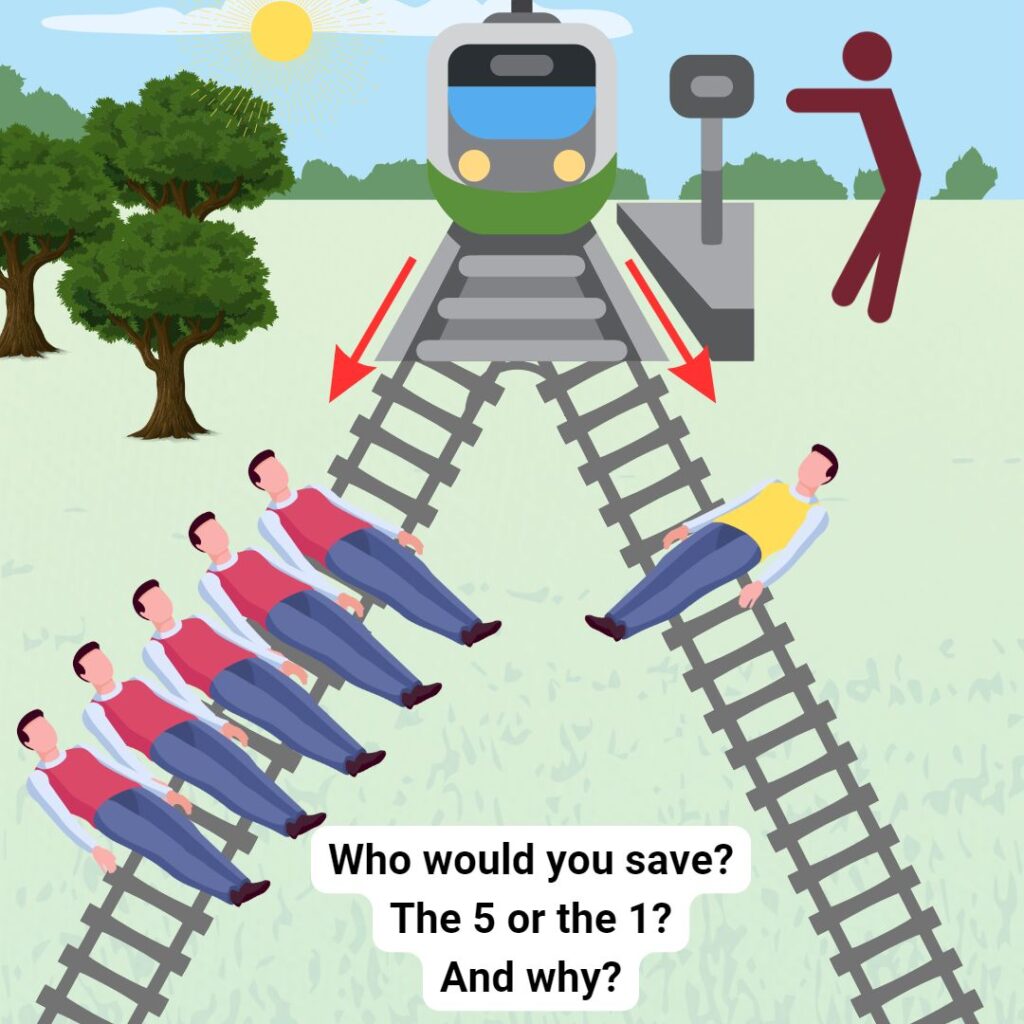

You live behind a railroad construction site. One beautiful morning, you go on a walk along the railway track, which is still under construction. On the railway, workmen are constructing two diversion lanes. While one worker fixes the left track, five workers are fixing the right track. They are very focused on their task. They are not disturbed by external noise since they are wearing earplugs. They can’t see you because they have their backs to you.

You’re miles ahead of them, whistling to yourself and watching the birds fly from tree to tree. You stop whistling as you spot a train speeding down the track in the direction of the construction workers. Unfortunately, any attempt to warn the construction workers of the approaching danger will be pointless. Their ears are sealed with earplugs. There would be no use in screaming at them. You can’t get there in time; it’s too far away.

Fortunately, right in front of you, there is a lever that controls which track is active. At the moment, the train heads for the left track, which has one construction worker. If you pull the lever, the active track is switched to the right, and the train will head on the right track, killing the five construction workers. Will you pull the lever to save one person, killing five people in the process? Or you won’t pull the lever, so one person will be killed instead of five?

Think about your answer. Most importantly, examine why you chose that particular response. Keep in mind that this is the simplest version of the trolley problem. In subsequent posts, we will discuss the metaethics of our various responses. The trolley problem will then progress to more complex versions.

A real life trolley problem

Would you believe me if I told you that just after I planned to draft this post, a friend of mine encountered a trolley problem? The concept in the flyer for this post happened in real life. Cobby left a comment on my WhatsApp status.

It was about the flyer I created for this post. Cobby responded to my status, ‘Till a loved one is the one killed, this is a puzzle. I’m currently in a situation like that, and it ain’t funny. Lost a friend. He’s yet to be buried.’ Cobby described his friend’s death as the driver of a car, in an attempt to avoid hitting one person, crashed into three more. Cobby’s friend was among the three pedestrians.

More trolley problems

Trolley problems are not trick questions. They merely serve to clarify how the circumstances of a situation impact our moral assessments. Don’t forget to include your response to the first trolley problem question. We’ll go over it in a future post.

What’s next in Peter’s Box? ¡Hasta luego amigos!