Pascal smiled at his reflection in the mirror. He could already see a promising, pleasant date with Edith. He applied his favourite cologne—savouring the notes in one deep breath and hoping Edith would love it too.

As the sun set over the ocean, Pascal looked at Edith from the corner of his eye. “Isn’t God wonderful?”

Edith sighed.

Pascal lightly tapped Edith’s arm. ‘‘No need to answer. I know what your answer would be. Why don’t you come with me to church tomorrow?”

Edith returned his smile. “But you know I am not Christian.”

Pascal's Invitation

“Yes, dear. I know you don’t believe in God, but I want you to do it for me.”

Edith stared once again into the vast blueness that lay before them. “That’s like asking a vegan to eat meat just because you like meat. You know very well that I do not believe in God and the claims of religion about a supernatural world.”

“Oh, Ed the analyst! How can you compare a harmless invitation to sit by me in church with asking you to eat meat?”

She noticed the disappointment on his face. “Going to church means going to listen to teachings and sermons that, for the most part, I do not agree with. You are asking me to consume information I don’t consider consumable. Would you visit the mosque to listen to Islamic teachings or visit a shrine to pour libation? Maybe once, yes, out of curiosity. But yours? It is not a one-time invitation. It is a calculated invitation to convert me by duress and not by reason. Just like most of my Christian friends would scheme.”

Pascal bowed his head. His lips quivered. “But if you love me, why are you finding it so difficult to just come with me? What do you lose? – absolutely nothing.”

Edith smiled into the thick blue seascape. “You are not the first person attempting this line of argument.”

“Ed, just pretend I’m inviting you out. Who knows? You might even begin to like the sermons and eventually believe in God.”

Pascal's Wager

Edith smiled at Pascal. “Your line of argument brings to mind a popular topic in Philosophy called Pascal’s Wager.”

Pascal turned to Edith. “Are you making fun of me?”

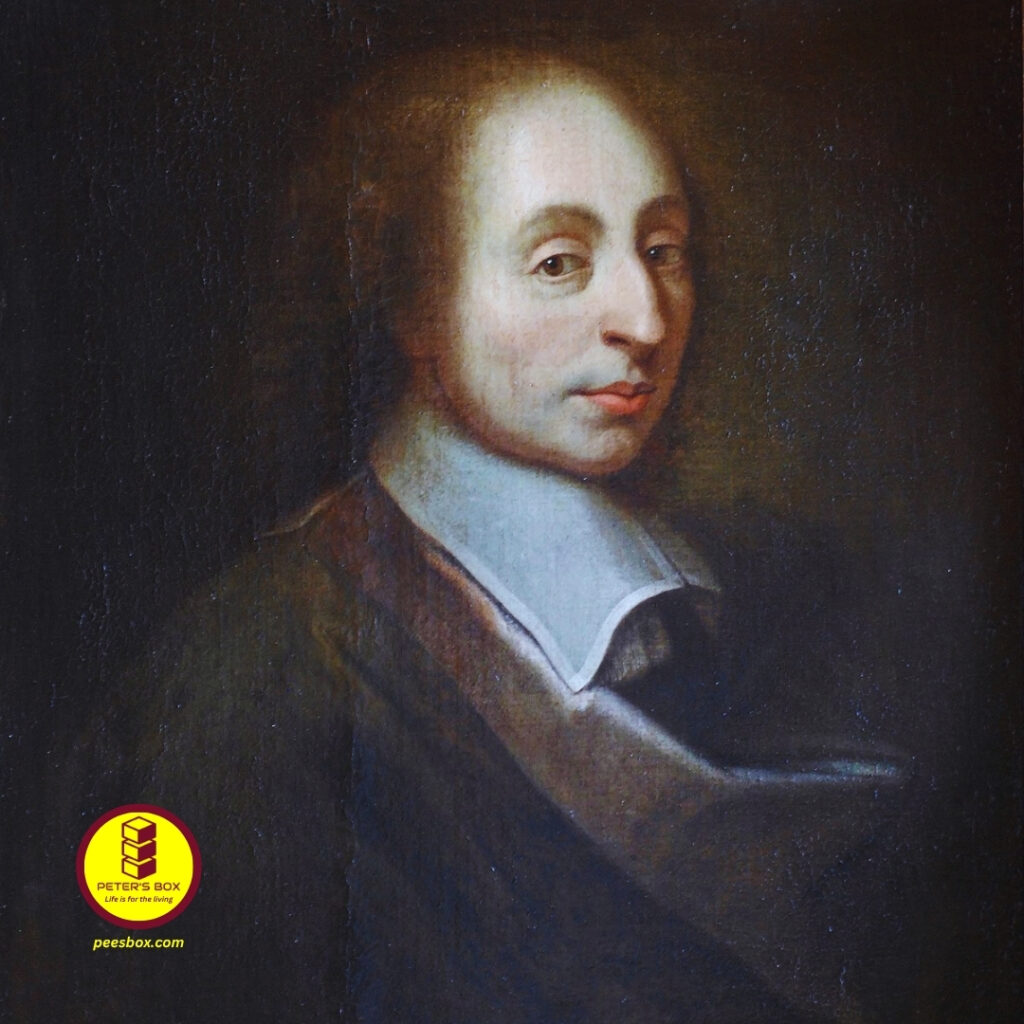

“Not at all! Blaise Pascal was a French philosopher, mathematician, scientist, inventor, and theologian. In mathematics, he was an early pioneer in the fields of game theory and probability theory. You’re familiar with Pascal’s triangle in maths, right? That was Blaise Pascal’s work. In philosophy he was an early pioneer in existentialism. As a writer on theology and religion, he was a defender of Christianity.”

Pascal’s eyes lit up. ‘See? Even a scientist believes in God.”

Edith raised her eyebrows. “And so?”

“Do you know better than scientists?” Pascal asked.

“I see what you did there, but forbear going down that path. You don’t even realise you are trapping yourself. If by your logic, because a scientist believes in God, I should believe in God, then if the scientist does not believe in God, then I should also not believe in God?”

Pascal looked at the white fluffy clouds, grateful that they sifted the bright afternoon sky. They greatly absorbed the heat of the arguments Edith gracefully flaunted.

Edith noticed his discomfort but continued. “You are cherry-picking, dear. But I am afraid to tell you that per your faulty logic you should not believe that God exists.”

Pascal squeezed his face. “How so?”

Edith stood up and extended her hand to Pascal. He took a cue and pulled himself up from the cool beach sand he had become accustomed to. She brushed some sand off his left elbow.

“Do you know that the majority of scientists in the scientific community do not believe that God exists? Let me ask you, Pascal, do you know better than scientists? Anyway, that’s not a good argument. Appealing to authority is not sufficient and is, in fact, a logical fallacy. What you should rather do is provide evidence or proof of your claim or the explanation of why the claim is true or false.”

Pascal replied, “But you mentioned that the scientist Blaise Pascal was a defender of the Christian faith.”

The purpose of Pascal's Wager

“Yes, he was. After his religious conversion he felt confident in his powers of argument and persuasion, both logical and literary, to affirm and justify Christianity against its detractors and critics. It would also be an exercise in his spiritual outreach and proselytisation – an earnest appeal, addressed to both the reason and the heart, inviting scoffers, doubters, the undecided, and the lost to join the Catholic faith. He viewed himself as an apologist and apostle.”

Pascal interrupted. “I am familiar with the term ‘apostle’, but who is an apologist?”

She replied, “…someone who speaks or writes in defence of someone or something that is typically controversial, unpopular, or subject to criticism. Early Christian writers who defended their beliefs against critics and recommended their faith to outsiders were called Christian apologists”.

Pascal nodded. “Ok, I get it now. So, what was Pascal’s wager?”

She responded, “Prior to his death, Pascal was working on a Christian apologetics book which was never completed. When Pascal died in 1662, he left behind several draft notes. They were edited by others, and the notes were first published in the form of Pensées in 1670. In one of his notes, Pascal developed the following argument. God is, or God is not. Reason cannot decide between the two alternatives. You must wager; it is not optional. Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. That’s what is termed as Pascal’s wager.”

“Can you expatiate?” he asked.

Edith responded, “Blaise Pascal contends that a rational person should adopt a lifestyle consistent with the existence of God and actively strive to believe in God. The reasoning behind this stance lies in the potential outcomes: if God does not exist, the individual incurs only finite losses, potentially sacrificing certain pleasures and luxuries. However, if God does indeed exist, they stand to gain immeasurably, as represented, for example, by an eternity in Heaven in the Abrahamic tradition, while simultaneously avoiding boundless losses associated with an eternity in Hell. Pascal’s wager is a philosophical argument that posits that individuals essentially engage in a life-defining gamble regarding the belief in the existence of God.”

What do you lose?

Pascal clapped enthusiastically. “Exactly what I have been telling you! You have absolutely nothing to lose if God does not exist but you believed anyway! However, you lose big time if God exists but you did not believe. You’ll end up in hell. Which do you prefer? Think about it.”

Edith laughed. “My dear, did you say I have nothing to lose? I have a lot to lose if God does not exist and I lived believing he did exist.”

Pascal crossed his arms over his chest. “Tell me about it.”

Edith kicked a clump of beach sand. “For starters, there’s an opportunity cost. I would have lost all the time I spent worshipping God, attending religious services, studying the Bible, and observing other religious duties. I could have spent that time hanging out with friends or learning a new skill or sleeping.”

Pascal puckered the corners of his lips. “But it’s not a huge loss. In fact, you would have been a better, decent human being after all. So, you lose nothing.”

Edith smiled. “I beg to differ. Steven Weinberg, an American physicist once remarked that ‘Good people do good, bad people do bad; but for a good person to do bad, it takes religion.’”

She waited for her comment to sink in and continued. “Pascal, I want you to think about all the evil things good people do, especially because of their religion.”

“Can you give me some examples?” he asked.

Good people doing bad

“There’s the suicide bombing community that is almost entirely religiously motivated. The mutilation of the genitals of infants is hugely influenced by religion. Last week I chanced on some horrific news. Fourteen members of a small religious sect in Australia were found guilty of the manslaughter of an 8-year-old girl, who died after they withheld insulin needed to treat her diabetes because of their unwavering belief that God would heal her. Instead of seeking medical help as she lay dying, they turned to prayer and song, maintaining a vigil around her bed, and even after she’d stopped breathing, sought divine intervention to raise her from the dead.

If it turns out that God doesn’t exist, the life of this little girl has been wasted. But even with the belief that God exists, see what it turns decent humans into?”

Pascal pinched his earlobe. “Well, they are not true believers. If they did, they would have taken the little girl to the hospital. God gave us a brain for a reason.”

Edith smiled. “Hah! I see. Fortunate for you that you would use your brain. Unfortunately for the little girl, some people decided to use their religion instead. That’s what I meant by good people do good, bad people do bad, but for a good person to do bad, it takes religion. It’s walking on a tightrope.”

Religion owns purpose?

Pascal affectionately squeezed her hand. “Well, I don’t think you would have wasted your time. I mean, you would have been edified spiritually and found meaning and purpose for your life.”

Edith squeezed back twice. “Are you saying that I don’t have any purpose in life? Why do believers think they have a sole propriety on the right way to live life and what purpose you should have in life? Purpose is what we imbue our lives with. I don’t think there is a singular grand purpose occupying time and space which is providentially allocated to us at birth. Purpose is an emergent property of the human condition – of the fact that we have to make sense of the world we live in.”

Pascal looked at his watch. “Don’t worry; let’s discuss this another time. I’m more curious about how confident you are about what you say you would lose if it turns out that God does not exist.”

How does God receive money?

She asked, “If God does not exist, what do you think would have happened to all my money that went to tithes, offerings, and the church?”

“It’s used for God’s work,” Pascal said.

Edith shot him an unconvincing look. “That’s what they tell you?”

“Well, they use it for God’s work,” he replied.

“Are you assuming, or do you know they use it as you say? By the way, I have always wondered how people are able to know what God wants in the first place. How many stories haven’t we heard in this country of religious leaders amassing wealth from their congregations?”

Pascal stopped walking. “Look, God doesn’t need money! He’s all-powerful. What does the creator of the universe need money for?”

“Ah, if your claim is true, let’s take the argument to its natural conclusion because you already have the answer,” she said.

Pascal was used to Edith’s Socratic way of dialoguing. “What do you mean?”

“Well, you say your God does not need money, so who needs them then?” she asked.

Pascal lingered a steely gaze at Edith. Edith batted her eyelid amidst an uncertain silence.

She turned to Pascal – the sunset silhouetting the edges of her hair. “My dear, you just said God doesn’t need money.”

Pascal looked bemused. “Uh-huh?”

She winked. “That means even if God exists, he wouldn’t need your money. Now do the math.”

Losing loved ones

Pascal looked at his wrist. “Apart from losing the time spent worshipping God and losing money that you would contribute to the church, what else would you lose?”

“I would have lost friends and loved ones. And I would have unfairly created enemies,” she said.

Pascal shook his head. “I don’t understand.”

“Am I not your enemy?” Edith asked.

A muscle twitched in Pascal’s jaw. The direction of the conversation was attempting to ruin his date. “Dear, what are you saying?”

“Does your Bible not say, ‘Do not be unequally yoked with unbelievers’?” Edith asked.

He wondered what Edith was up to. “Where does it say that?” he asked.

Edith took out her phone. She googled 2nd Corinthians chapter 6 verse 14. “There you have it.”

Pascal was impressed. “How come you know so much about the Bible?”

Edith said, “Have you forgotten I wasn’t born an unbeliever? I was raised a Christian, so I know what it is like to think like a Christian. Besides, 1st Peter, chapter 3, verse 15 says, ‘But in your hearts revere Christ as Lord. Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect.’”

Pascal clasped her hands in his. “I love you regardless of whether you are an unbeliever.”

She closed her eyes. “Yes, you do. But you can’t live with me.”

“Your point?” Pascal asked.

Dating Pascal's Wager

Her eyes were still closed. “I’m only telling you how your religion treats unbelievers like me. You are not the first Christian to fall in love with me.”

“What was your experience like dating believers?” he asked.

She opened her eyes. “Simple. It gets nowhere.”

“Why?” he asked.

“They concede that they can’t start a family with an unbeliever.”

“Oh, really?”

“Yh. They say they would only marry me if I convert to Christianity. I used to be frustrated and disappointed at them, but these days I am unbothered.”

Pascal’s eyes fogged up. “I love you, hun.”

She looked away. “I know. But your faith won’t allow you to be with me.”

“But…”

“That’s what I meant by ‘I would have lost friends and loved ones. And I would have unfairly created enemies if I believed that God existed but it turned out not to be true. Anyway, what if you are wrong about God’s existence? Have you ever thought about that?”

Pascal ducked and pointed at her. “What if you are wrong too and I am right?”

Blind fault in Pascal's Wager

“Well, there are many faults with Pascal’s wager. Let’s meet up again to discuss it if you are ok with that,” she said.

“Hmmm, that’s fine. I’ll prepare well for you next time. What’s one big fault you find with Pascal’s wager?” Pascal said.

“I call it the Blind Fault.”

“Ed the Philosopher! I wonder why you offered engineering at the university.”

“When I read Pascal’s wager, I realised Pascal was referring to his God throughout.”

Pascal crossed his arms over his chest. “And what’s wrong with that?”

“He assumes his god is the right god. What if, in the end, the god of Islam is the one true god? Or the god of another religion? Pascal blinded himself to the gods of other religions. He only saw his God,” she said.

What’s next in Peter’s Box? ¡Hasta luego amigos!

I really enjoyed how you wove philosophy into such a relatable, human conversation. Edith’s perspective was powerful yet graceful, and Pascal’s sincerity gave the dialogue real warmth. The balance between heart and reason made me stop and reflect. Truly thought provoking, yet beautifully told.

Then wait for the second part. It gets even more exciting.